Steve Cushing Impresionist Fine Art Photography

Embracing imperfection, recording emotions, one impression at a time…

- Images-Imperfections

- A.Schacht Ulm 90 f2.8

- A.Schacht Ulm 135 3.5

- ASchacht MTRAVENAR

- Anamorphic LOMO 110

- Asahi Takumar 17 f4

- Berthiot Flor 200 f4.5

- Canon 50 f1.2 RF

- Canon Dream 50 f0,95

- Canon 50 f1.8 Leica

- Canon FD 50 f1.4

- CZ Biogon 35 f2.8

- CZ R-Biotar 50 f0.7

- CZ Biotar 58 f2

- CZ Biotar 58 PreWar

- CZ Biotar 75 f1.5

- CZ Flektogon 20 f2.8

- CZ Pro Tessar 50 f2.8

- CZ Pro Tessar 115 f4

- CZ Sonnar 50 f1.5

- CZ Sonnar 85 f2.0

- CZ Sonnar 135 f4

- CZ Sonnar 135 PreWar

- CZ Stereotar Stereo

- CZ Stereo-System

- CZ Triotar 135 f4

- Cyclop H3T 85 f1.5

- Deltamar 70 f1.6

- EF 100mm f/2.8L USM

- EF 100-400 f/4.5L IS

- El-Nikkor 50 f2.8

- El-Nikkor 50 f4

- Elicar V-HQ Medical

- Ernemann Ernostar f2

- Fujinon 55mm f2.2

- Helios 44 (KMZ)

- Helios 44 58 f2

- Helios 65 50 f2

- ISCO Ultra MC 65 f2

- ISCO Ultra MC 85 f2

- Jupiter 9 85 f2

- Jupiter 11 f4.0

- Kilfitt Makro-Kilar 40

- Konishiroku 35 f2.8

- Konica Hexanon 260

- Leitz Wetzlar AV90 f2.5

- Mayer AV 80 f2.8

- Meyer 100mm f2.8

- Mir-1 37mm f2.8

- MC Rokkor 24mm f2.8

- MC Rokkor 28 mm f2.5

- MC Rokkor 58 f1.2

- MD Rokkor 135 f2.8

- Noflexar 35 f3.5 Macro

- Olympus Zuiko 50 f1.8

- Pentacon 28 f2.8

- Pentacon 50 f1.8

- Pentacon 135 f2.8

- Pentacon 200 f4

- Pentagon AV 80 f2.8

- Pentagon AV 100 f2.8

- Pentacon AV 140 f3.5

- Petzval LOMO 130 f1.8

- Rayxar e50 f0.75 Delft

- Rodenstock Heligon

- Rodenstock Rodagon

- RF 50mm f/1.2L USM

- Rollei Projar 85 f2.8

- Schneider 50 f2.8

- Schneider 75 f4.5

- Schneider 135 f3.5

- Sigma 14-24 DG Art

- Steinheil 135cm f4.5

- Stitz Stereo SV-1 3D

- Stitz Stereo IR SV1 3D

- Super-Takumar 55 f1.8

- Super-Kiptar 90 2.0

- Tair-11 133 f2.8

- Triplet 5 AV 100 f2.8

- Will-Wetzlar AV 90

- French Life

- Aigues-Mortes

- Bardou

- Bédarieux

- Bédarieux Stereo

- Boussagues

- Boussagues Stereo

- Brenas

- Cabreroles

- Caroux Stereo

- Cirque de Mourèze

- Cirque Mourèze Stereo

- Colombieres-sur-Orb

- Colombieres Stereo

- Douch

- Estaussan

- Faugeres

- Faugeres Stereo

- FOS

- FOS Stereo

- Gabion

- Château Grézan

- Gorges d'Heric

- Gorges d'Heric Stereo

- Herepian

- Herepian Stereo

- Herepian Rally

- Herepian Cycling

- Madale de Rosis Stereo

- Minerve

- Minerve Stereo

- Montpellier

- Music Prieuré StJulien

- Olargues

- Olargues Stereo

- Passa Pais

- Passa Pais Stereo

- Pezanas

- Pézènes-les-Mines

- Pézènes Stereo

- Roquebrun

- Saint-Julien

- Saint-Martin-de-l'Arçon

- St-Martin-de-Londres

- St-Martin-de-Londr 3D

- St Guilhem le Desert

- Vieussan

- Vieussan Stereo

- Villemagne-l'Argentaire

- Villemagne Stereo

- Created Imperfections

- IR and UV Selected Range

- Lenses

- Asahi Takumar 17 f4

- A.Schacht Ulm 90 f2.8

- A.Schacht Ulm 135 3.5

- ASchacht MTRAVENAR

- Anamorphic LOMO 110

- Berthiot Flor 200 f4.5

- Canon 50 f1.2 RF

- Canon Dream 50 f0.95

- Canon 50 F1.8 Leica

- Canon FD 50 f1.4

- CZ Biogon 35 f2.8

- CZ R-Biotar 50 f0.7

- CZ Biotar 58 f2

- CZ Biotar 58 PreWar

- CZ Biotar 75 f1.5

- CZ Contaflex

- CZ Flektogon 20 f4

- CZ Flektogon 20 f2.8

- CZ Sonnar 50 f1.5

- CZ Sonnar 85 PreWar

- CZ Sonnar 135 f4.0

- CZ Sonnar 135 PreWar

- CZ Stereotar Stereo

- CZ Stereo-System

- CZ Triotar 135 f4.0

- Cyclop H3T 85 f1.5

- Deltamar 70 f1.6

- EF 100mm f/2.8L

- EF 100-400 f/4.5L IS

- El-Nikkor 50mm

- Elicar V-HQ Medical

- Ernemann Ernostar f2

- Fujinon 55mm f2.2

- Helios 44 (KMZ)

- Helios 44-2 58 f2

- Helios 65 50 f2

- ISCO Ultra MC 65 f2

- Jupiter 9 85 f2.0

- Jupiter 11 135 f4.0

- Kilfitt Makro-Kilar 40

- Konishiroku 35 f2.8

- Konica Hexanon 260

- Leitz Wetzlar 90 f2.5

- MC Rokkor 24 f2.8

- MC Rokkor 28 f2.5

- MC Rokkor 58 f1.2

- MD Rokkor 135 f2.8

- Meyer AV 80mm f2.8

- Meyer 100mm f2.8

- Mir-1 37mm f2.8

- Noflexar 35 f3.5 Macro

- Olympus Zuiko 50 f1.8

- Pentacon 28 f2.8

- Pentacon 50 f1.8

- Pentacon 135 f2.8

- Pentacon 200 f/4

- Pentacon AV 80 f2.8

- Pentacon AV 100 f2.8

- Pentacon AV 140 f3.5

- Petzval LOMO 130 f1.8

- Rayxar e50 f0.75 Delft

- Rodenstock Heligon

- Rodenstock Rodagon

- RF 50mm f/1.2L USM

- Rollei Projar 85 f2.8

- Schneider 50 f2.8

- Schneider 75 f4.5

- Schneider 135 f3.5

- Sigma 14-24 DG Art

- Steinheil 135cm f4.5

- Stitz Stereo SV-1 3D

- Super-Kiptar 90 2.0

- Super-Takumar 55 f1.8

- Tair-11 133 f2.8

- Triplet 5 AV 100 f2.8

- Will-Wetzlar AV 90

- Tech Blog

- Aberrations

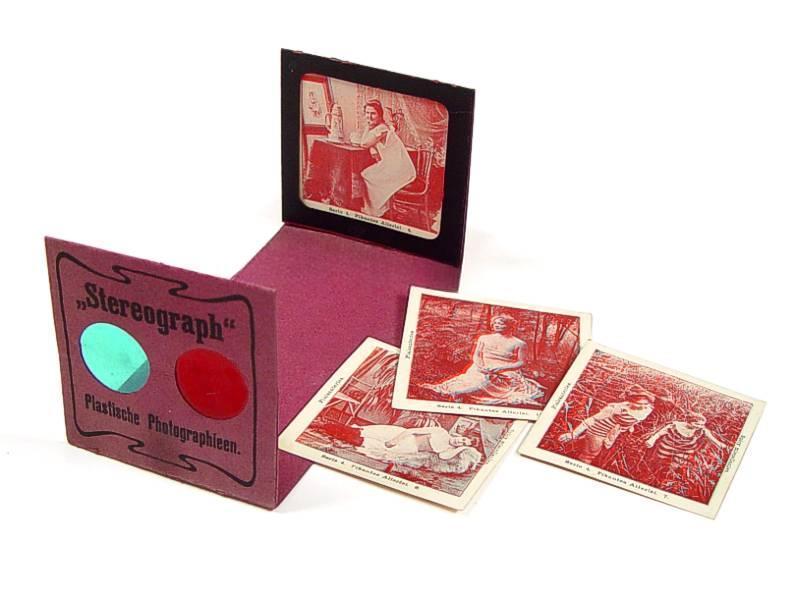

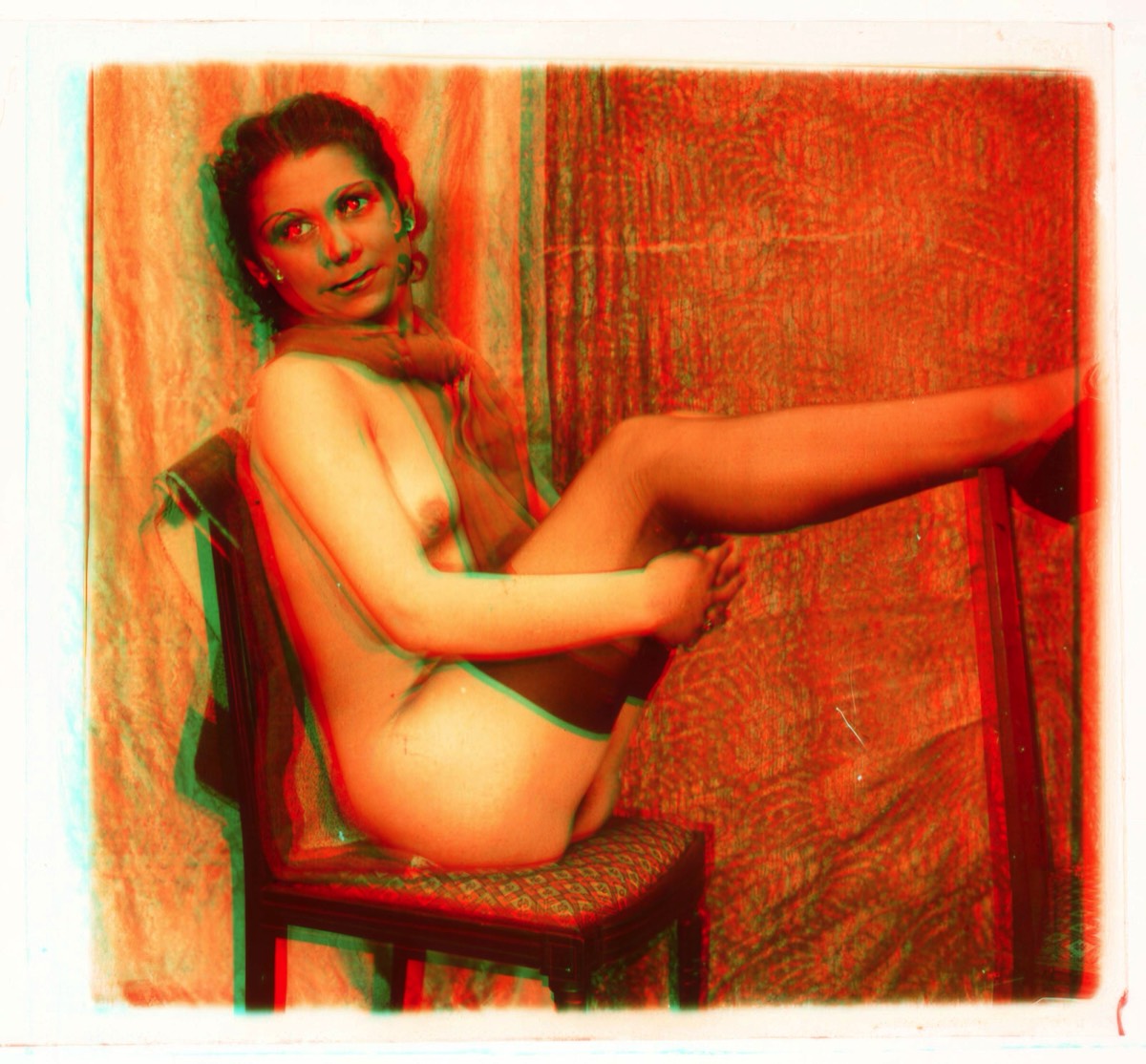

- Anaglyph 3D

- Anamorphic Lenses

- Aperture

- Aperture and Lens Size

- Exposure

- Bokeh

- Cha-Cha Stereo

- Chromatic Errors

- Creating Adapters

- Creative Techniques

- Crop Factor

- Dating Lenses

- Depth of Field

- Digital Sensors

- Extension Tubes

- False Colour

- Fast Lenses

- Film VS Digital

- Fine Art Photography

- Flange Distance

- Flange Distances (list)

- Focal Length

- Focal Plane

- Focus Stacking

- Helicoids

- High Dynamic Range

- How Lenses Work

- Hyper Stereo

- InfraRed Photography

- Influencies Art

- Influencies Photos

- ISO Speed

- Lens Cleaning

- Lens Design and Glass

- Lens Design History

- Lens Flare

- Light and Photography

- Manual Lenses

- Maximum Aperture

- ND Filters

- Optical Lens Types

- Painting Photographs

- Perspective

- Projector Lenses

- Radioactive Lenses

- Resolution MTF

- Shutter Speed

- Stereo Photography

- Stereo IR Photography

- Stereo Window

- Tilt and Shift Lenses

- UV Photography

- Vignetting

- Visual Language

- Wet Plate

- Zoom Lenses

- Contact

- Cushing Tree